An interview with James Finley by Ryan Kohls Feb 17, 2023

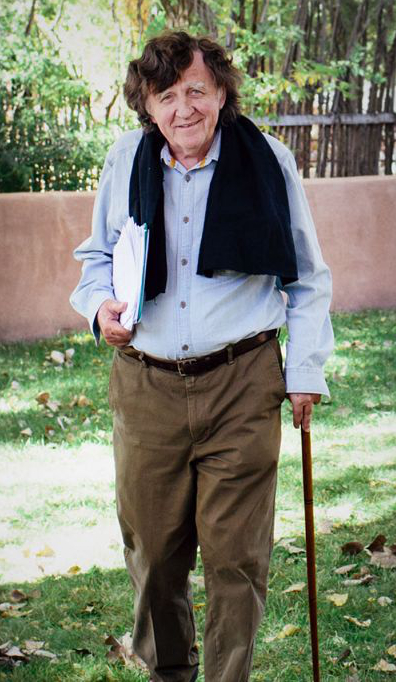

“God does not exist,” says James Finley, the renowned Catholic mystic who has dedicated most of his existence to studying, writing and talking about God

Wait…what? Oh, there’s more.

“There isn’t some infinite being called God who exists,” he adds. “God is the name that we give to the beginning-less, boundary-less, infinite plenitude of existence itself. I am who I am. God is that by which we are.”

Putting Finley’s mystical philosophy in a box is a useless exercise. It’s ever expanding and defies classification. And that’s just the way he likes it.

Born in Akron, Ohio in 1943, James Finley’s life is filled with paradoxes. His childhood was steeped in trauma as his father, a violent alcoholic, preyed on him and his mother. Yet it was amidst this hell that Finley found solace in mystical experiences. Raised Roman Catholic, Finley was taught to pray and seek God in times of trouble. In doing so, Finley began a profound and healing relationship with mystical Christianity.

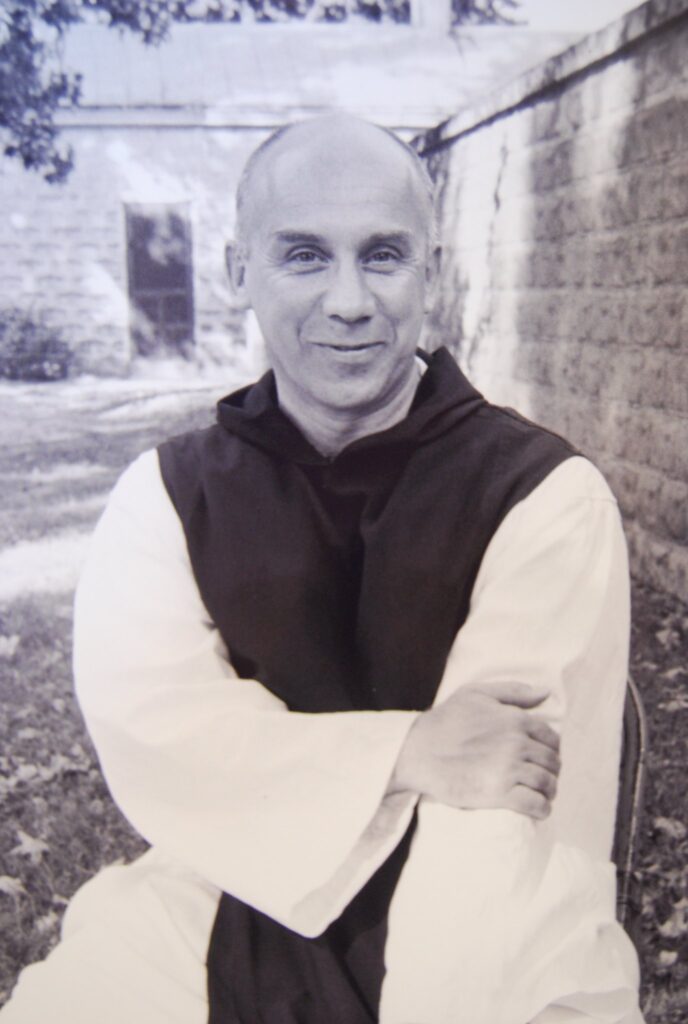

At age 14, Finley’s life was forever transformed when he stumbled upon Thomas Merton’s book ‘The Sign of Jonas‘. Merton — a Trappist monk based in Kentucky — had risen to prominence with best-selling books documenting his spiritual journey and life in the monastery. Merton’s story resonated deeply with Finley and he felt called to follow in his footsteps. After graduating from high school, he immediately left home and entered Merton’s monastery at the Abbey of Gethsemani.

For nearly six years, Finley lived in virtual silence at the monastery. Here he studied the world of mystical Christianity and meditated extensively. He even received spiritual direction from Thomas Merton himself. Merton’s influence also extended outside of Christian teaching and Finley was introduced to the mystical lineage in other world religions like Hinduism, Buddhism, Judaism and Islam. It was radical stuff and in turn Finely was radicalized into this worldview.

At the monastery, however, another tragedy hit Finley. One of the priests who he’d become very close with began to sexually abuse him. The experience was disorienting for Finley and a new wave of trauma overcame him. Soon after the assault began, without saying a word to anyone, he resigned from the monastery. He had envisioned spending his whole life there, but suddenly was out.

At this point it would surprise no one if Finley began to hate God, hate the church and perhaps even hate himself. Yet another paradox emerges: in the face of all these painful experiences the love and hope he found in his faith remained intact.

Since leaving the monastery, Finley’s walked an inspiring and impactful path. Through his studies he earned a Ph.D and became a practicing clinical psychologist and has dedicated his energy to educate and help those who seek closer commune with God and spiritual tools to face their trauma. He’s written several books including ‘Merton’s Palace of Nowhere: An Ultimate Identity Beyond the Ego’ and ‘The Contemplative Heart’ and his forthcoming memoir ‘The Healing Path‘. He’s also a core teacher at the Center for Action and Contemplation (CAC); a non-profit school “introducing seekers to the contemplative Christian path of transformation.” On top of teaching, he hosts a podcast for the CAC called ‘Turning to the Mystics‘, where he introduces listeners to key Christian mystics like Meister Eckhart, Teresa of Avila and St. John of the Cross.

I was first introduced to James Finley by way of Richard Rohr; the Franciscan monk, best selling author and founder of the Centre for Action and Contemplation. Rohr became a gateway to others like Finley and the fascinating mystics that influenced them. What struck me immediately about Rohr is the same thing that caught me with Finley: I sensed a deep humility and sincerity in the work. To put it another way: their egos seemed in check.

There is much I WANNA KNOW from such an enlightened thinker. So, I caught up with Finley via Skype from his home in California.

From mystical experiences, to psychedelic drugs, to Thomas Merton, to the importance of interfaith dialogue, to the roots of pain and trauma, we cover it all.***

As a way of introduction, I’m curious how you define yourself. Do you consider yourself to be a Christian? Are you a mystic? Are you a Christian mystic? Does any of that apply to you in any meaningful way?

I most directly identify with the Catholic tradition of the Christian faith, and in particular with the mystical lineage of contemplative, mystical Christianity. Also with a spirit of openness to the mystical lineage of all the world’s great religions. I was six years in the cloistered Trappist monastery of Thomas Merton and while I was there Thich Nhat Hanh came from Vietnam to talk with Merton and through that I was introduced to the Dharma. Abraham Joshua Heschel, the Jewish mystic and philosopher, also came. And I got very involved in medieval philosophy and the reading of Judaism and in the reading of Martin Buber. Merton was very into dialogue with mystical Islam, with the Sufi tradition; Rumi and Hafez.

I deeply identify with and have been enriched by these traditions. But I most identify with the Christian mystics that have transformed me: Saint John of the Cross, Teresa of Avila, Meister Eckhart, Julian of Norwich. And also in my work as a clinical psychologist, where spirituality is a resource of healing and transformative to the depth dimension of the healing encounter. So, I would describe myself in those terms.

I was first introduced to your work through your podcast ‘Turning to the Mystics.’ In one episode, at the end, you lead listeners in a meditation and ask them to repeat this phrase: “Be still and know that I am God” and then slowly take away the words until you just get down to the word “Be”. And I was sitting in my apartment by myself, and I closed my eyes and I did what you told me to do, Jim. And I have to say that what happened to me, I can only describe as a mystical, transcendent experience. And I just remember thinking whatever you could have hoped the best case scenario for that moment would be, it happened. And I just want you to explain what happened to me?

Here’s one way that I would put it. Our faith tells us that God is here now about us and within us. St. Augustine is closer to us than we are to ourselves. And in faith we interiorly assent to that. In our heart we believe there’s a deep truth in that. What happens in moments like this is you intimately experience what faith proclaims. How I put it mystically: it’s like unexplainably resting in God resting in you, where somehow you and God mutually disappear dualistically as other than each other. And in that moment, you become a momentary mystic. Then, you experience the wonder of this all-encompassing oneness that transcends and permeates our life, only you taste it directly for yourself. And I think that’s what it is. It’s like an inner quickening in your heart.

Why do you think that the recipe of repeating that phrase can lead people into that kind of state?

My sense of it is this. That phrase “Be still and know that I am God” comes from the Psalms. So you ponder on your bed and be still. Thomas Merton is in the monastery, and at the time we slept in a common dormitory. He’s lying there in his cell and he had insomnia. And then he says and suddenly the bed becomes an altar. And in a distant city somewhere someone is suddenly able to pray. And so I think the whole ethos of monastic life, the chanting of the Psalms, the silence, the simplicity, the seeking of God, kind of opens up the heart to that.

There’s another piece of it also with the bell. It was a Buddhist meditation bell. It’s the power of ritual. There’s something about a liturgy of the body. Let’s bow in reverential gratitude. Thomas Merton once said with God a little sincerity goes a long, long way. When we bow in communal gratitude the least and the most we can do is surrender ourselves over to the gift and the miracle of being alive right now, together like this. The ringing of the bell is a sound that tapers off into silence. We’re kind of tapping into ancient archetypal primordial patterns that invite this awakening.

You write in your memoir, ‘The Healing Path’, about some of these mystical experiences you’ve had. And you say it’s almost superficial when you try to put it into words. But if you had to try — when you transcend — how would you describe it to those who have no clue what we’re talking about or long for something like that but don’t even know what to look for?

I want to say first some examples of how we do experience it. But because it’s so subtle, we don’t tend to notice the implications of what we’re experiencing, which would be a mystical experience in the broad sense. We tend to think of mystical experiences as intense things that mystics speak of. And people say, I’d never experience that. But like you said, the way you experienced it when you recited ‘Be still and know that I am God’, your heart can be quickened unexpectedly with the taste of it.

Let’s say that you’ve been fortunate to be in a deep marital love relationship. That has been for you so transformative and profound and life changing; just immense gratitude. And you get a phone call from someone you knew in high school. You haven’t heard from the person in years. They say they’re passing through town and want to catch up. And you’re talking, you’re sharing with each other about your work and what’s happened. And you tell this person about this relationship and this person, about how you met, about the person’s character. You show the person the pictures of what the person looks like, and the person says but what I’d like to know is this: Who is it that you know the person to be, not factually, but in your love for this person? And all of a sudden you realize that nothing you could say would do justice to who you know the person to be in love. And your heart breaks when you try and you’re graced to be strangely made whole by having your heart broken by this love that can’t be expressed adequately in words. That’s mysticism. It’s like the unexpected nearness of the upwelling of a gift that cannot be explained washes over you and it touches you.

Thomas Merton, at the end of ‘New Seeds of Contemplation’, gives a litany of examples of this. He says imagine you’re about walking along somewhere in the midst of nature, and you turn to see a flock of birds descending. And he says, as if out of the corner of your eye, you catch in their descent something primordial, vast and true. And you’re anteriorly quickened in a kind of a subtle enrichment of awareness, a sensing that in some way you can’t explain God is the infinity of the intimate immediacy of the birds and their descent. And the burden of descent is the concrete immediacy of God. And the concrete immediacy of God is in you being awakened to that. And you’re moved to just sit down and sit there for a while, like what in the hell was that? I can’t say it, but having tasted it, I will not break faith with my awakened heart. I will not play the cynic. In an unexpected hour I was quickened with this oneness. He says sometimes it can happen also in the presence of a child, reading a child a good night story, you’re just literally unravelled by the presence of this child. We’re sitting in the presence of a dying loved one, like the mystery of it all. We’re lying awake at night listening to the rain pour down all about the house and the sense comes over you like this.

I think we all have moments like this, but we don’t live in a society that teaches us to become students of these moments. And because what starts to happen for some people with these touches is the desire to abide in the depths so fleetingly glimpsed. And having tasted the oneness that has the feeling of that which never ends, what would be a path or a way of life where could I find someone well-seasoned in such things that could guide me? And this is the guidance of the mystic. Turning to the mystics for guidance. They offer practical advice like how to discern that it’s happening to you because sometimes it’s so subtle. You don’t calibrate your heart to a fine enough scale to pick it up. And then how can you cooperate with it? How can you go along with it and be transformed by God in the ordinariness of your life? That’s the feeling that it has for me.

It almost aligns with this concept of being born again. I can speak on behalf of my own experience coming out of those moments and just looking through the world with different eyes. Does that ring true to you at all?

Yes. There’s a translation of Eckhart’s teaching called ‘Wandering Joy’, and the person who wrote the foreword, David Appelbaum, says at the beginning that by the time of Jesus it was already ancient. We must be born again. In this moment, when it’s actually happening, it’s too deep to comprehend, it’s too self-evident to doubt and we’re born again. Jesus said, you must be born again because we’ve become exiled from it.

Here’s another way that I put it too. In the momentum of the day’s demands, just the complexities of life, most of the things we notice, we notice in passing on our way to something else. And then you get the feeling that you’re skimming over the surface of the depths of your own life. What’s regrettable is God’s unexplainable oneness with you is hidden in the depths over which you’re skimming. But in moments like this, like a hiatus in sequential time, you’re born again. This is what the word religion means: to be bound to the origin. And we need to be reborn because we’ve been exiled from it. How can I be reborn to this upwelling of this flowing out of this divine generosity, which alone is ultimately real? And how can I be more habitually sensitive to it and responsive to it so I can live it every day and share it with others by the way I treat them and listen to them and walk the earth?

Is there a particular moment you’d be comfortable talking about where you experienced something mystical?

I’ll share one. In the monastery — this is a cloistered Trappist monastery — we got up at 2:30 in the morning chanting the Psalms. We practiced silence. When I was there, we didn’t talk at all. You use sign language. We listened to God. And it was a life of prayer, silence, simplicity, and manual labour seeking God to give ourself to God. And believing that inner fidelity to that seeking touches the whole world in ways we don’t understand. That was the way.

Merton was my novice master. He led me in this and led me into the mystics. One winter Sunday it had snowed a lot. And on Sundays we were allowed to walk across this little country road that cut through the monastery land and go into these expansive woods on the other side. And I sat in the snow at the base of a tree. I sat very, very still. When I put my head back against the tree and I looked up to the bare branches and I could see the snow falling down to the bare branches. And it was so silent I could hear the snow hitting the leaves. And while I was sitting there a full-grown deer came by with a head full of antlers. It turned and looked right at me, but I was sitting so still that he didn’t see me. And my heart was pounding because I knew if I scared it, it could hurt me. I was sitting there on the ground and it walked right past me on through the woods. And I looked up to the bare branches of the trees and silently within myself I said to God, is this the way it is with us? And looking up through the bare branches and the snow coming down from unseen places in this gray sky, I’m looking right at you, but I don’t see you. And if I don’t see you, I don’t see myself either or the snow or the trees. Because I am your manifested presence in the world. Help me. And I just sat there like that for a long time, given over to that. I got up and walked back to the monastery and chanted Vespers. There were a lot of moments like that for me in the monastery. And then when I left, I wanted to continue living that way. I set aside a quiet time every day so that I could stay grounded in that depth dimension of my life.

When that moment is happening what kind of physical state are you in? Is there full body numbness, for example?

I would say psychologically it really varies. Sometimes you can burst out laughing, sometimes just the gift of tears. Sometimes you start crying. Sometimes you’re numbed at one level, but only because you’re highly energized at a more interior level. Like you’re deeply awake. It’s a heightened state of consciousness. It spills over into the body in different ways and emotions and memory. But you can tell as it spills over it has reverberations and emotions, but it’s deeper than emotions. It spills over into insights, but it’s deeper than what thought can comprehend. It’s like you’re betwixt and between two worlds. It’s like a gate of heaven. And then you say, well, what would be the path that I could live in an underlying habitual sensibility to this oneness that I know is always there? Which is the path.

There’s a big conversation these days about psychedelic drugs, like marijuana or mushrooms, being spiritual tools to get you to that mystical place. Many often describe an experience of oneness. What is your take on psychedelic drugs? Do you believe they are spiritual?

First of all, they’re often not spiritual because they’re addictive and they’re destructive. And it’s kind of a confusing burden to a lot of people. But they can be awakening and there’s more and more awareness of cannabis and other drugs in treatment of disease, in pain management. And there’s a lot of neurological research being done on that. And it has religious connotations in certain indigenous cultures, a mood-altering substance to heighten these mystical states.

This is my sense with the drugs, like cannabis, and this was Merton’s insight too. It’s true it awakens the physiology of these experiences. But unless your character is open to being surrendered over to God, you get caught in the physiology of the experience, but it doesn’t translate into holiness. It doesn’t translate into a Godly person who lives in the love nature of God in every breath and heartbeat. And that’s the problem with it. I was just reading Evelyn Underhill’s ‘Mysticism’ this morning and she starts out her classic work distinguishing between magic and religion. And she says, the art of magic is the heightening of powers for yourself. You’re drawing power to yourself. Religion is surrendering ourselves over to the abyss like mystery of this love, transforming us into itself unexplainably. Religio: to be rebound. And that’s the trouble is it so easily becomes magic. We get stuck there. But it does have the potential to be an awakening experience of the mystical where the person then seeks it in prayer and meditation in daily life.

Are drugs something that you’ve dabbled with in your spiritual practice? Has it been a part of your routine at any point?

No. For 30 years my wife — who died two years ago of Alzheimer’s right here at home — was an alcoholic. She gave me permission to break her anonymity. It saved her life, essentially. We lived right at the beach. The ocean’s right outside the door. Every evening at sunset we would sit out there. She would have iced tea or something and I’d have a glass of wine or some alcoholic drink. And I would write one of my mystical texts. There’s something about the ritual of wine and quietly sitting with the sunset, with the beloved. But with marijuana I never really got into it. During my first marriage, when I left the monastery, I tried it two or three times, but I didn’t care for it for some reason. But just recently, I got a joint. They opened up a joint store right around the corner. I tried it about three times. It’s okay. I tend to be very relaxed anyway, so it didn’t do much for me.

I don’t need to have my consciousness altered. I know some people I worked with in therapy, musicians and creative people, they claim that a little bit of marijuana helps heighten the awareness. It all depends if you do it in moderation and why you do it.

I’d agree that they can be very useful for spiritual or creative purposes, but perhaps to avoid addiction it’s best to also find sober ways of searching for mystical experiences?

I have an online course that’s going on right now at the Centre for Action and Contemplation called ‘Mystical Sobriety’. It’s the mystical dimension of each step of Alcoholics Anonymous. We’re all addicted to habits of the mind and heart that cause suffering. I work with a lot of addicts in my therapy practice and my meditation group. The 11th step is conscious contact with God. They would come to the meditation for that. The alcoholic makes an amazing discovery that their problems are not their problem. It’s their consciousness of the problem. And they discover by alcohol they can alter their consciousness. And once they alter their consciousness it numbs them to the problem. But the trouble is, it numbs it in the wrong direction. It numbs it by distancing them from the ability to be grounded and face their life. And then they’ve got two problems. They have the problem of addiction and they’re powerless over it. And it’s taking their life. And secondly, the developmental growth of their own maturity stops. This is why when a person comes to sobriety through their higher power, they’re freed from dependence on the substance, then they face the emotions that they drank not to feel in the first place. They have to face their fear and their anger and the rage and their self-pity. They have to show emotional sobriety, which then leads to spiritual sobriety and transforms their life.

Shifting gears, let’s talk about Jesus Christ. Would you define Jesus as a mystic?

Yes. I would say theologically, Jesus is the Christ. The word made flesh and dwelt among us. Whatever it means to be God, whatever it means to be human, are now entwined inseparably into a unitive mystery. So in Christ it’s revealed that God’s response to us in our dilemma is to become identified with us as precious in the midst of our dilemma.

But experientially, another way of looking at it is Jesus was a Jewish mystic. Here’s one way that I put it, by prayerfully reading the Gospels and Jesus: What if we could close our eyes and we could be interiorly awakened so that when we opened our eyes we could see through our own awakened eyes what Jesus saw in all that he saw? What would we see? We’d see God. Because Jesus saw God in everything. And what’s really mysterious about it when you sit with the Gospels, it didn’t matter whether he was seeing the joy of those gathered at a wedding or sorrow of those gathered at the burial of a loved one. It didn’t matter whether he saw a prostitute or his own mother. It didn’t matter whether he saw his disciples or his executioners. It didn’t matter whether he saw a bird or a flower. Jesus saw God in all that he saw. And Jesus said you have eyes to see and you do not see. There is your God given capacity to see the godly nature of everything around you and you don’t see it. And this is a source of all your sorrow. This is the source of all your confusion. And the prayer is Lord that I might see. Lord that I might see through my own awakened eyes your presence right before me and everything that I see, the godly nature, the concreteness of things.

Is Jesus Christ, in your view, the greatest mystic of all time? Or is it counterproductive to even create a hierarchy?

The mystery of being a person is the mystery of the infinite presence of God presencing itself. Being endowed with the capacity to recognize God as being given and poured out as life itself. So that we might, in seeing the generosity of God and the diversity of the immediacy of everything, be moved then to give ourself in love to the love that gives itself to us in every breath and a heartbeat. Because love is always offered, it’s never imposed. And that’s universal and religious consciousness.

But the language that a person uses to express that awakening is in an historically, culturally specific way. And when it emerges in India, it emerges in the dispensation of yoga. Namaste. When it emerged in the Buddha, it emerged as the Dharma. The Four Noble Truths. And in Judaism it emerges in the deepening of Torah and the prophets. And then in Jewish mysticism, Kabbalah. And so in Christianity, it emerges in the Christian mystics. We would say theologically the overwhelming image is God, the word made flesh dwelt among us revealing all of this to us. But for the Buddhists, the all encompassing image is the Buddha sitting all night on the night of his enlightenment and the cessation of suffering when he turned and saw the daystar. He saw the purity of the phenomenal world, boundary-less and pure in all directions. Thomas Merton put it this way, the world will not survive religion based on tribal consciousness. But those who take the religion all the way to its hidden centre find that the tradition transcends itself in this realization of God. And when they move toward this hidden centre — the Hindu, the Jew — through contemplative prayer through silence of perpetual surrender, they recognize each other at the centre.

There was a series a long time ago called ‘The Long Search.’ And this person spent a year living with people in the different religions of the world. He spent a year in Saudi Arabia. He lived with a Muslim family and the Imams. Then for a month in Israel, he lived with a Jewish family on a kibbutz. He was in southern France with a Catholic family. And he said that he got the impression that if all these religious people could all get together at once in one place it would be an argument so loud, you couldn’t hear yourself think. But if he could gather together the handful of people that had the most profound effect on him when he was in their presence that there’d be silence and a deep respect for each other. And when they did speak, there wouldn’t be any attempt to convert or change anybody but to each bear witness in his or her own way, and this overwhelming plenitude of this deep awakening.

And I think that’s very close to what Merton’s sensitivity was to it. Merton once said the regrettable thing about the Christian missionary movement is that all too often the Christian missionaries failed to realize the people they were converting were as or more holy than they were. And this is at the heart of Richard Rohr too; the Living School and the new orthodoxy of love. For us that’s our path as Christians. It’s Jesus. I have to keep the eucharist here at my home and I have icons all over the house, and I walk around with my rosary all day long. But I’m also deeply at home with the Dharma. That’s where I’m at.

Do you believe Jesus would be disappointed that many Christians have seemingly misinterpreted his teachings or worship him in a way he might not have wanted?

At the Last Supper there was a traitor at the table. Things weren’t off to a good start. And hanging on the cross. What’s the view from the cross? You look out going what the hell is going on here? You know? This intermingling of brokenness with the preciousness that permeates the brokenness and can touch the heart and break hearts open so the light shines through. Remember me when you come into your kingdom said the thief hanging on the cross next to him. This day you’ll be with me in paradise. Father forgive them for they know not what they do. And I think that’s the mystery of the gospel. We’re infinitely loved, broken people, and the deep acceptance of our brokenness is the opening to which the tender-hearted mercy of God enters our life as repentance and faith. And it isn’t as if we’re trying to live up to something. We get discouraged because we never live up to it. Rather, we’re not taught to put our faith in our ability to live up to the standard. Rather, we’re to place our faith in God who is infinitely in love with us in our inability to live up to the standard.

Thomas Merton once said we should always meditate when we’re discouraged after a fall, especially if somebody saw it and we lost our temper. And he said because what it reveals is our secret agenda: a holy me. You could do something like that. But ‘moi’? And what it does is exposes this internalized image of ourselves we’re trying to put forth. And instead, we’re trying to let this light of infinite mercy shine through the image so we can let go of it. It’s not that I am who my father told me I was, or my mother or my lover or my spouse or my pastor. And the images isn’t who I think I am. How can I join God in knowing who God eternally knows me to be hidden with Christ in God before the origins of the universe? That’s what matters. How can I do that?

Do you think Christians are missing those insights though because of a tribal hold on Jesus as exclusive truth? And how problematic has that been for the message?

I think that is often true. But I think God is present in their life. You know, we’re all walking around in the midst of our limitations. And to devotional sincerity the presence of God is real. He walks with me and he talks with me and he tells me I am his own. It’s real and it’s efficacious, but it’s within these often unacknowledged limitations of this tribal thing. The word Catholic means universal. It’s ever more inclusive. It’s not a belief system dependent. And Thomas Merton said the real way to study Buddhism is not to read a lot of books on Buddhism it’s to meet a holy Buddhist. And the real way for them to know Christianity is not to read a lot of theology books and footnotes on the Gospel it’s to meet a holy Christian. And this holiness is this child like radicalized transparency, this gratitude intimately lived and shared day-by-day. And I think that’s what we’re all trying to move towards.

Thomas Merton seems quite revolutionary in his interfaith work. Just how ahead of his time was he? And what was his worldview on other faiths?

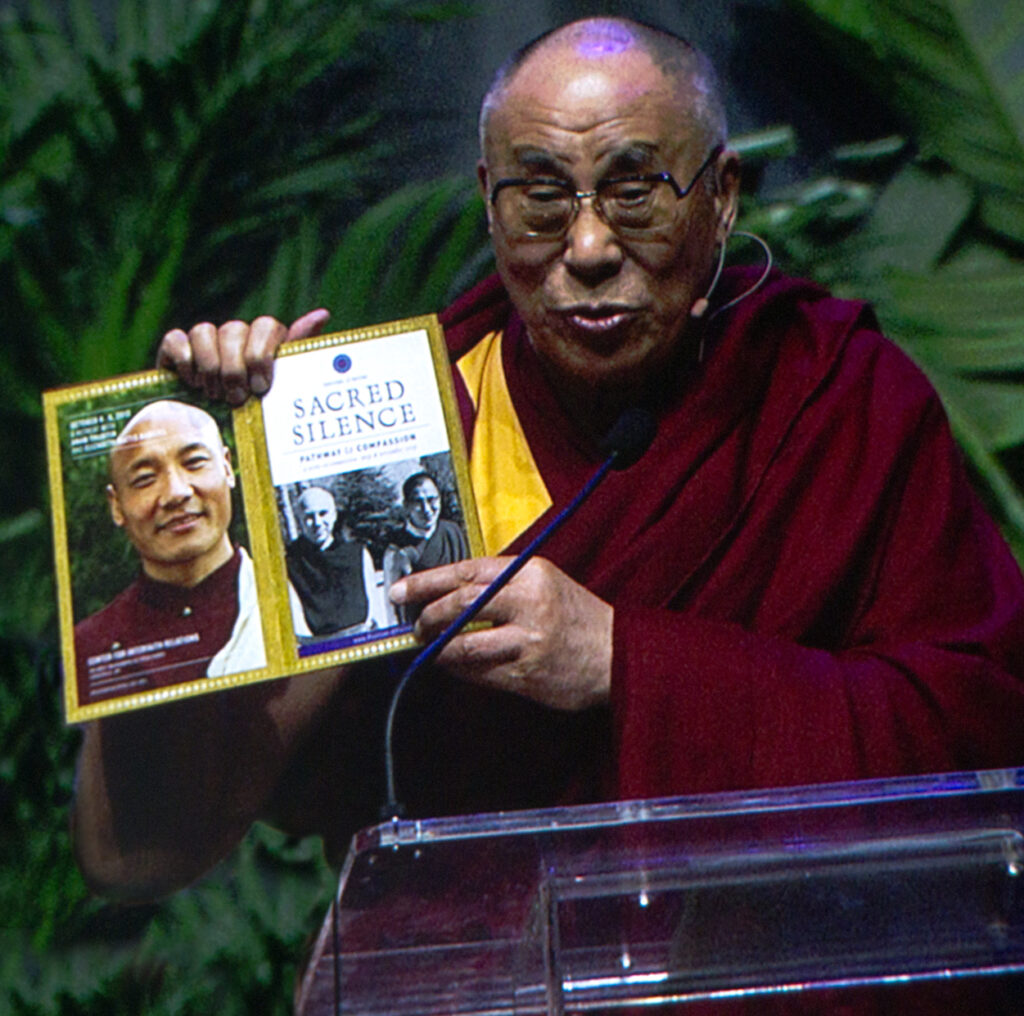

You know, I think he changed. In his autobiography ‘The Seven Story Mountain’ there’s a lot of Catholic triumphalism. The truth of the Catholic Church. I studied medieval philosophy from Dan Walsh, who taught philosophy at Columbia. Merton sat in his classes. And then Walsh came to the monastery and taught metaphysics at the seminary. I got the philosophical theology of Thomas Aquinas and Bonaventure and scholars and it had a very deep effect on me. And Dan Walsh said once in a class, all human beings must seek the truth, except Catholics. They know the truth. That’s Catholic triumphalism. You see flavors of that in Merton. But he really changed in his late 50s, early 60s. There’s that conversion experience where he was in Louisville for medical treatment standing at the intersection of a street. He said he suddenly realized he loved all those people. And he wrote a book called ‘Seeds of Destruction’ against the Vietnam War, against atomic weaponry. He wrote a book on these deeply social issues. He became also deeply interested in this dialogue with non-Christian traditions. That we have so much to learn from each other. That’s why he went to Asia and he met the Dalai Lama.

He died on that trip. He was electrocuted. Just before he died in his Asian journal he wrote, the more I’m with my Buddhist brothers and sisters the more I appreciate my faith in Christ. May Christ live in the hearts of all of us. It wasn’t leaving Catholicism, but it was a universal Catholicism that included the presence of God in these pathways of Buddhism and Hinduism. He said I believe the time is coming and is already here when a person will identify with more than one religious tradition at once. He said, I believe this is the work of the spirit moving through the world. That makes sense to me.

There’s great mystery surrounding Merton’s death in Thailand. He was such a radical and popular thinker who pushed anti-war messages. Some people really believe that the US government, or the CIA, assassinated him. Do you give much thought to those theories? Or is that something you try to ignore?

There’s a lovely hour long video on the mysterious death of Thomas Merton. He researched it in depth and he was talking with a person who was there when Merton died. And I think it’s entirely possible that our government, the CIA, killed him. But we don’t know. You can watch the video of his last talk and he said, I shall disappear. And he went up to his room and he was to give a question-and-answer period that night but he didn’t come down. He was in Bangkok, Thailand, and there was a fan high up on a windowsill. And they think he went over to turn the fan towards the bed. And when he grabbed it there was a short in the fan. And he grabbed it and he fell back and the fan fell on his chest. When he didn’t show up, they went into the room and saw him lying there and he had died. What happened? Was a short put in the fan? We just don’t know. I think it’s entirely possible.

How does one know when they’re being called to be a mystic or to devote their whole life and being to the thought and the study of this kind of stuff? How can you discern that?

There’s mystical reverberations in the life of all of us. The sense of the reverberations of an unexplainable fullness of presence. The presence of God that kind of illumines and re-energizes us, our faith and our life. But when it comes to the calling, here’s how I put it: that which is essential never imposes itself. That which is unessential is constantly imposing itself. But sometimes these inner quickening that we’ve been talking about, this taste of oneness, there’s a higher order wisdom of our awakened heart and it becomes something personal for us. And a person doesn’t plan this. Thomas Merton once said there’s many people who are being led in this direction, but they have no one to help them to understand what’s happening to them, no one to give them encouragement and guidance.

For some people they can’t explain it. A person might say, for example, unless I spend some time each day in a quiet rendezvous with God — like here I am Lord — unless I’m faithful to this rendezvous in your presence I will not be who I believe deep down I really am. And I’m called to be. And there’s an obedient fidelity to this. And when I read the Gospels, when I read the mystics, I can tell they’re talking about what I long for, and I can use them to guide me and to help me. And when I open the Gospels and read the Gospels at this level, this deep level, it resonates within me. Sometimes I’ll say that everything that Jesus says is interiorly recognized like falling off a cliff. We will never, never, never, never get to the bottom of anything because it’s the abyss like depths of God’s voice in the world speaking to our heart. But when we approach it out of our ego it’s like a wall of granite. You can’t see past it. For some people it just becomes an inner calling. And where can I find a community of people, a meditation group, a prayer group? That’s what I think our podcast ‘Turning to the Mystics’ is, like a monastery in cyberspace. There’s a collective recognition of each other and words of collective encouragement on this path. Such a person isn’t more holy than others. But it’s a deepening realization of how unexplainably holy everybody is.

You’ve studied a lot of mystics. It doesn’t really seem like these people ease their way into this life. Something dramatic happens. Is there always a moment or experience where the calling becomes a burden or it becomes a tunnel vision focus?

This is the value if you can find a contemplative spiritual director because we’re subject to self-deception. For some people, the lure toward the mystical can be a way of finding a rationale for distancing themselves from the concreteness of their own life. That happens fairly often. But if it’s really authentic, it actually radicalizes and grounds us in the strength of God to face our own life. It takes the art of discernment. Is the direction I’m moving in helping me to be more grateful, more humble, more patient, more empty handed, more receptive to learn? Then it’s probably genuine. If I’m more judgmental, more closed off, maybe we should take another look.

When you start to feel like you’re awakened or enlightened you often have a desire to tell other people. But if you’re really good at articulating these experiences and this history, like yourself or Richard Rohr, you can become a celebrity. You’ve said before you were starstruck by Thomas Merton. How do you make sense of that side of things? The messenger can almost become an idol or worshiped in a way.

The mystic way does not draw attention to itself. As a matter of fact, sometimes you meet somebody, like a grandmother or a grandfather, and you get the feeling you’re in the presence of a deeply present person. But they’re anonymous. There’s just the transparency of their goodness or their love or their inner clarity. But some people are called to be mystic teachers. Not only have they been given this gift of oneness, but they’ve been given the gift of finding words that helps other people find their way. And a lot of these gifted teachers are contemplative, spiritual directors that are also unknown. But once in a while, somebody gets a wider audience and they become a mystical celebrity, like Richard Rohr or Thomas Merton or whatever. It has to do with name recognition. It’s not artificial, but it’s kind of a product of what happens when your teachings are exposed to a lot of people. Then a lot of people respond. And if that happens to you, it’s to not buy into it. It’s God’s will.

I’d be giving these silent retreats and people would come up to me and shake my hand and they would say to me, I’m so honored to be in your presence. And one voice inside says, really? I’m just trying to get through another day. Another voice inside says now don’t hold back feel free to express yourself. I love being in the presence of people who are honored to be in my presence. And on a deeper level, I know what they’re really talking about is the presence of God. And that’s what they’re really talking about. You see it mirrored in somebody. Thomas Merton was once speaking about Zen masters and said we recognize it in somebody and so when you sit with the master, the teacher accepts the recognition. The master also knows what you recognize in them is completely true of you, but you’re not ready to hear it. You won’t believe it. And therefore, out of compassion as a temporary arrangement, they accept. In the Buddhist tradition, they have the tradition of slapping the master. You don’t actually slap the master, but it’s a gesture because you’re delightfully unemployed, because there’s no master. It shines out of you in your ordinariness. God raises people providentially with a wider thing, but it’s just one-on-one, you know? It’s just heart to heart.

I guess if someone is still an asshole you can discern they’re not that enlightened, right?

You can be an enlightened asshole. You just haven’t integrated your brokenness into the enlightenment. You can use it to sexually abuse people. You can use it to exploit people. It calls for perpetual conversion always. In his Asian journal, Merton said, from time to time it happens that someone breaks through into God. He says someone recognizes that person’s breakthrough, the mystic, and they sit with that person. And there was formed there in that place a contemplative community that no one can ever destroy because it’s not composed of compound things. It’s not composed of empire or structures. And let’s say you’re living in a heartfelt way. You’re on this journey and someone comes up to you and says, do you mind if we talk for a while? You say sure and you walk up the road together. This talk you and I are having right now, sure, let’s talk like this. And there’s formed here in this moment a contemplative community that no one can ever destroy. And that’s how the lineage, I think, is handed on endlessly throughout the world. Heart-to-heart.

When many people turn to meditation and seek this oneness it’s often in times of pain or confusion or when the world feels really heavy. You’ve written before that “we’re here to learn how to love, and then God breathes us back into the infinite love.” But part of that process of learning to love though is so much pain and suffering. Why do we need this experience of being here learning to love?

There is a sense of the brokenness of human nature, like original sin, but not as a blight on the soul. There’s a sense we’re experientially exiled from the upwelling of this love that’s sustaining us breath by breath. The word trauma means a wound. Our capacity to abide in the self donating love of God sustaining us, breath by breath, is traumatized. And in that traumatized state, we act out the traumatizing things we do to ourselves and to each other. There’s that and there’s the moral imperative. We’re always working towards being a non-violent, protective, nurturing person that doesn’t contribute to suffering. And when suffering does occur, how can I ease the burden of the suffering in myself? And how can I go to someone who can help me, a friend or a mental health person.

But here’s the key to this. That often is true. It often comes welling up out of suffering. For me, in my memoir, it started for me when I was three years old and my father was very was a violent alcoholic. And my mother was a devout Catholic. And when she would take us to mass on Sunday and say ask God for the strength when Daddy gets mad. That’s how she put it. And one night I was lying in bed about three years old, and I heard him hitting my mother outside the door in the dark. And I prayed the way frightened children pray. And I experienced that God heard my prayer, came to me in the dark and merged with me. That was my experience. And throughout my life this sense of God merging with me deepened and sustained me through the trauma.

I discovered Thomas Merton in the ninth grade. The ‘The Sign of Jonas’ had a profound effect on me. When I graduated from high school, I was moved to the monastery. And then when I left the monastery, I wrote a book called ‘Merton’s Palace of Nowhere: An Ultimate Identity Beyond the Ego’. And when that book came out, it was 1979, I was invited to give a silent retreat by a clinical psychologist John Finch, and I gave the retreat on Merton and the true self. I was a high school religion teacher at the time, married with two little children. He said if you’d be willing to commit yourself to the contribution mystical traditions make to mental health, I’ll see to it that you have a Ph.D. with family support as a gift, not as a loan. And I moved from Cleveland, Ohio, to out here to California and five years of full time doctoral work. And I became a full time therapist. And the people I saw were mainly trauma survivors who wanted their spirituality to be a resource in their therapy. I watched very, very carefully how sometimes you sit in the very midst of the healing journey and the light can shine through. And when we risk sharing what hurts the most in the presence of someone who will not invade us or abandon us, we can learn not to invade or abandoned ourself. That’s true. We can be re-parented in love. But also, what can happen even deeper is what Jesus called the pearl of great price. In the risk of sharing what hurts the most there comes welling up an intimate realization of being unexplainably precious in my brokenness, and I can learn to live by that preciousness. And that’s where I think this the deep psychological touches, the spiritual, they merge with each other and in an integrative way.

Your story is one of overcoming great trauma and pain and turning it into beauty and into hope. But so many people don’t seem to get there. They commit suicide, they live and die in abject hell. How do you reconcile the fact that so many people never channel it in the beautiful way that you’re describing?

That’s true. Many people don’t. My understanding is this. How can I become a healing presence in an all too often traumatized and traumatizing world? How can I heal the world one person at a time? First of all, the people I live with, the community and so on. But many people they die in that state. I believe that when they die in that state and they pass through the veil of death, the healing occurs in eternity. But often it doesn’t occur here for a lot of people. It just doesn’t.

But how do you make sense of that?

What I make sense of is that it doesn’t make sense. Not everything makes sense. A lot of life makes no sense. Meaning, how could you adequately explain or justify it in a way like oh, I get it. That explains it. Thank you. I’ll move on to my next question. It’s not a question that calls for an answer. It’s a question that calls for a response of your whole being to be open to the mystery. And how can I follow this path and how can I let God use me to serve God’s purposes in the world by my own fidelity transformation like that? Look at the war in Ukraine. Look at racism. But I think it’s always been this way. I mean, look at Jesus. It was the Roman Empire and the crucifixion. The world is a divine, elegant, beautiful, brutal, cruel, brief, and unfair place. It always has been. Marcus Borg wrote a book called “Meeting Jesus for the First time”. It’s about the last week of Jesus based on the gospel. And he gave this image. He said Pontius Pilate was coming from Rome as procurator to preside over the Jewish people with soldiers and armor. Coming from the other side in Jerusalem was Jesus riding on a donkey. And people were waving palm branches. He said the real question in life is which parade you belong to. That’s the question, because both parades are always there, and sometimes both parades are in our own heart. The bittersweet alchemy of our own culture of perpetual conversion and humility. That’s the mystery that Jesus lived in. God so loved the world, not the ideal world, he entered into this world. God sent his only begotten son, which is the holiness of this world in this brokenness. And how can we bear witness to it?

Many people don’t engage with the idea of God or religious concepts because of how brutal existence can be. Where do you stand on the origins of suffering?

Let’s say there’s a person who’s an atheist, who looks and says how could there even be a good God with all this evil happening? It makes no sense. They don’t buy it. And that’s just what they are. That’s their faith. So the atheist doesn’t know there’s no God. They have a kind of a faith that there’s no God. I say I’d like to talk about something else first before we talk about this. If there’s somebody in your life that you love very much. I want you to think of that person. And also think of your gratitude for that person in your life. And also know that although you could explain a lot of things about this person, there’d be something that made it closer and closer to the heart of the matter that you could not explain. I see that as religion. When a husband tells his wife, I love you. She doesn’t say, define your terms. Or she doesn’t say I didn’t know that let me write that down. She didn’t say, you said that yesterday. You’re so repetitive. Then why do they say it over and over to each other? Because every time they say it, they reawaken to each other the love that the words awaken and embody. It’s like a mantra. It depends on what we mean by religion. I think religion is what gives meaning and value to our life. Bernard Lonergan says religion is a lot more like falling in love with someone than it is proving something. Where is that person’s sincerity? Let’s start there. And even though they don’t believe in my language for it. That’s okay. We just take each person where they are.

As we’re speaking, there’s been this incredible tragedy with this earthquake where 40,000 people, and counting, died in the blink of an eye because the earth shifted and opened up. How do you make sense of tragedies on a scale like that?

For anyone who’s a trauma survivor this is true. Whatever it means that God takes care of us, it doesn’t mean that God takes care of us in protecting the bad thing from happening. It doesn’t. That’s the mystery of the cross. And that’s why I say God is a presence that protects us from nothing, even as God unexplainable sustains us in all things. But before the question can arise with meaning, we need to sit in silence first to come to this interior depth dimension out of which to speak in a meaningful way. And all those people that died they’re eternal because no one ever dies. Everyone created by God lives forever in God. But our life and ego consciousness is a temporary arrangement. But can we find in the fleetingness of our life that which never passes away and sustains us like the eternality of the fleeting of things. A tragedy is a tragedy. It’s a nightmare. You see the response of people coming in, trying to help like the goodness of humanity. And none of us are protected. When I got up this morning and put my feet on the floor. There were many people who went to bed last night with big plans for the day, they didn’t wake up this morning. And they’re eternal in God. When my wife died, when the beloved crosses over, the land between birth and death becomes more transparent. Like the beloved is gone, but at a deeper interior level, the lover is just as close and one with each other in an unexplainable way. And I’m not stuck here either, because soon I’ll be joining her. I’ll be 80 years old in May. And what’s the celestial nature of the day by day, and how can I live life on life’s terms? And then how can I increase conscious contact with God through the unexplainable complexities of life?

If I’m hearing you correctly it’s the belief and hope that we are all eternal and united with God, so death is nothing to overly worry about?

Can I learn from God how to die to everything less than an infinite union with God as a final source of my security and identity? And I cannot go alone because the survival instinct is too strong. But can I learn through meditation and prayer and love? Can that thread that keeps me connected become more and more delicate? John of the Cross once said a bird held by a single thread is just as much a prisoner as one held by great rope if it won’t break the thread. And we can’t break that pattern ourself, but sometimes love breaks it through bliss, through loss. The light shines through and we get a foretaste of a fullness. And here’s the thing about it. In the moments we see the flock of birds descending or where we hold the beloved in our arms, or we lie in the dark listening to our breathing, we’re in the nearness of a presence that doesn’t have about it the feeling of that whichever ends. That’s what I think is so significant. It doesn’t have about the feeling that it has boundaries. Like we could go out to the edge of it and find where it stops. It’s beginning-less, boundary-less, deathless, and intimately realized in the depths of my heart. And as I learn to live by that, I think approaching these questions at that level is a spiritual dimension to the temple order and psychological warfare.

You were raised in the Catholic tradition. I heard Richard Rohr say once that Catholics have made an idol out of the Pope. And I look at the Pope today, Pope Francis, who’s considered to be progressive in terms of Catholic thinking. He said recently that homosexuality is not a crime, but a sin. And that was seen as a very radical thing for a Pope to say. But do you think the Papacy should be abolished as it may be a relic holding back the progression of the message?

No, and I don’t see it that way at all. Does he say it’s definitely a sin? I don’t think he said that.

I think he said homosexuality is not a crime, but it’s a sin.

Wow. That’s too bad he said that. Here’s how I see it. If you look at the Roman church it’s very ancient and it’s very big. It’s very complicated. Cardinal John Henry Newman talked about the evolution of doctrine. And he says doctrine evolves through the epochs, through time. And when it comes to sexuality. I think we’re really in the midst of an age where there’s been a standard thing about homosexuality being condemned, that it’s wrong. If you’re born with the male body, you’re a man. If you’re born with the woman’s body, you’re a woman. It was all set. And I think what’s happening is we’re kind of in the midst of transitioning into another new way of seeing all of this. Things like sexuality and sexual orientation. Martin Heidegger puts it this way, in the spirit of the age, there is the energy that brings about that age. There is the spirit that sustains the age, keeps the status quo going, and there’s the energy that brings about the end of the age. And what brings about the end of the age clouds within it the energy that is the spirit of the next age. When you’re between two ages, there’s conflict. There’s those who try to hold on to the way it used to be. Like homosexuality is a sin. And there are those that are rethinking the whole question in a new way about sexuality, the mystery of it, the orientation of it.

But I think the day is coming that we’ll be eventually moving to. Here’s how I put it kind of tongue-in-cheek. God could have saved the world so much trouble if he just would have made Jesus a woman. Seriously. And you say to Jesus, the 12 disciples, what were you thinking? Why not make six of them women and six of the men? Religion transcends the bias of the culture, but religion is also culture bound. And that conflict between is very mysterious and theologically subtle.

Right now there’s a huge debate in secular circles and religious circles about being transgender. What do you think about people who come out and try to transition into a different gender and believe they were born in the wrong body?

First of all, it’s complicated. And this is especially so with people who feel this way in their adolescence. There’s the whole question of when you’re old enough to make a responsible decision and so on. But there are people, say men in a man’s body, who interiorly experience themselves to be a woman. That’s their experience. And there are women who know themselves to be men. That’s their experience. And I think it’s experiencing the atypical expressions of sexuality. We’re just at the beginning of understanding it and how to responsibly work with it.

There was a big article in the Wall Street Journal that one of the wealthiest corporate business people in the world is a woman who used to be a man. This person is a worldwide leader in pharmaceutical work and also owns SiriusXM radio. Martine Rothblatt. I met her and she’s a brilliant, wealthy, gifted, grounded person who had to courageously walk that walk and be that way. I’m not knowledgeable in this. I was a clinical psychologist, but I’m not studying the journals. These are simply my ways I would tend to start to approach the question as a clinical psychologist and someone who would come to me and say the way they experience themself. And it’s to respect that and then try to understand it better and help them find their way. It’s not my business. It’s not my life.

What do you think about gender pronouns for God? Do you still use “he”?

This comes up in writing a lot too, when you’re writing a book and God is he and she. Gender does not apply to God. God is infinite presence itself transcending terms that apply to us, but not to God. However, because God is the creator of gender, the infinity of the mystery of being a woman and a man is in God and is divine. And there’s a kind of historical patriarchal dominance of men over women. Part of it is just physical dominance and political dominance like an all-male clergy in the Catholic Church, for example. What I would like to see is the church reactivating women deacons in the church. In the early church women were deacons. Then you’d have women in holy orders. Next, in the shortage of priests. You would ordain some of the women as priests and married people as priests. And if you just continued that and moved along in those lines, eventually this present set of assumptions would fall into the background. These things are very ingrained.

But the thing about the church is no concern of mine. I don’t care about it. But mystical Catholicism, you know, this divinization of the self in the Eastern and Western church, I am deeply Catholic in that sense. But I’m a layperson. If I were a priest, I’d have to be more engaged at that level. But I don’t care. I respect it, the devotional depth of it. But these things have no concern because they’re not real. I’m so used to working with people in therapy one-on-one, like, tell me what hurts let’s talk. And it’s lay back the layers one at a time and let’s find our way. I tend to deal with things at that level.

You work at the Center for Action and Contemplation with Richard Rohr. I’m wondering if you could tell me a little bit about your relationship with Richard and the influence he’s had on your spiritual life and thinking.

When I left the monastery and wrote ‘Merton’s Palace of Nowhere’ I got word Richard Rohr, who was very widely known on the circuit, liked my book. And we met on the circuit several times and I saw that what Merton achieved in reawakening the timeless lineage of contemplative Christianity, Richard Rohr was reawakening it as a Franciscan monk in the world. I saw him as a living missive with a mystical depth of pastoral sensitivities. I was invited several times to lead retreats with Richard. I was invited to the Centre for Action and Contemplation and the Living School. The Living School is basically a commitment to daily contemplative prayer and meditation, an in-depth study of the Christian mystics and translating that into a form of service to the world. There’s no exams, nothing, just personal enrichment, the transformation of your life. They listen to the talks on the classical texts by the teachers. They have dialogue with each other and so on. I identified with it as just contemplative Christianity and action in the world. And I’m so grateful for Richard who is my dear friend and we keep in close touch. He’s kind of in a very fragile but very good place in his life right now. So it’s just like he’s just been a dear friend of mine and companion, along with the other teachers, Brian McLaren, Dr. Barbara Holmes, Mirabai Starr, these other teachers. And it’s just home base for me.

Richard Rohr is stepping back from public life because of his health. How is he doing?

I think this is fairly public. For a while there he was with a cancer diagnosis. People were worried about him and he was declining. But they found a new treatment. And he’s really rebounding in terms of energy level. He’s pain free. I don’t think he feels called to get back to administrative work with the Centre for Action and Contemplation again. But it’s like a new phase of his life. He’s doing well.

Do you think Rohr’s legacy will be in the lineage of a Merton for future generations?

I do. Back centuries ago, there was a movement of the Beguines. They were contemporaries of Meister Eckhart. Really great mystical works as a quickening or deepening of mystical Catholicism. And I think that we’ll look back at Thomas Merton and Richard Rohr and the Living School, in the history of Christianity, as the reawakening of the contemplative, mystical dimensions of discipleship in the world. I think it’s timeless.

Some people listening to this would be very skeptical of these mystical experiences we’re talking about and say perhaps we are placing meaning in a meaningless world. What do you say to people who approach you with that sort of naysayer attitude?

As Dr. Phil would say, how’s that working for you? And if you think that’s nonsense, why don’t you share with me something in your life that isn’t nonsense? Your love for your children, your spouse, your work. Let’s talk about what gives meaning and substance to your life. You don’t have to believe that. At least show that you’re interested enough to want to know more about it. And if you’re not, we have no basis to talk. I don’t want to waste your time talking about something you don’t want to know about. The real question is the quality of their life and their goodness and their character and what they do live by.

Dan Walsh used to say at the monastery, the cynic communicates nothing. And if you are going to criticize something, it’s good to show some awareness that you have knowledge about what you’re criticizing. But if you have no knowledge of it, it might be wiser just to be quiet about things you don’t understand because you’ve never even tried to understand it. Why be disrespectful? I would think it would be wiser to refrain. You could say I personally don’t identify with that. That makes sense. But to sweep it away I think it’s better not to do that.

If you listen to the greatest atheist thinkers they can’t rule out 100% that God doesn’t. They would never say 100%. You study this stuff, you’ve experienced this stuff, you’ve inspired people to look into it. Is God real? Is there any doubt left within you after all these years?

You can’t get at it logically. In a strange way you say God is all about us and within us, closer to us then we are to ourselves, but we look around and there’s no God in sight. But also notice that if I am with somebody who is my beloved, I see the body of the beloved and the personality. But what it is I know them to be, and my love for them, I can’t see it. I can’t explain it. I can’t. And I would like to bring that sensitivity to it.

I would say, God does not exist. There isn’t some infinite being called God who exists. God is the name that we give to the beginning-less, boundary-less, endless, infinite plenitude of existence itself. I am who am. God is that by which we are. And furthermore, God is a presence in an ongoing self-donating act that’s presencing itself and utterly giving itself away in and as the gift and the miracle of the intimate immediacy of our very presence. The closer we can start to get to it are these moments of awakening we spoke of earlier, like these awe moments of quickening, like a door opens and a light shines through is a way to explore it. If you yourself are inclined to do that or not, that’s not my business. Because if I could prove it, it wouldn’t be God. Thomas Merton once said, the person who says prove it not only are they not at bat, they’re not even in the ballpark. If you’re capable of proving it, it would be infinitely less than what we’re talking about. We don’t prove it, but we intimately bear witness to it. Thomas Merton once said the most important things of life are often the things we can’t explain to anybody, including ourselves. But there are certain things you simply have to accept as true or you go crazy inside. And they’re the very things of the intimacy of the unexplainable. And we learn to live by. Dan Walsh used to say at the monastery, I know it I know it and I know that I know it. But the trouble is, it’s I that know it and when I try to tell you what it is that I know that I know, I don’t know what to say. And this is the voice of lovers. This is the voice of poets. This is the voice of mystics.

That’s beautiful. And maybe the best way to end it is the way you end every chapter in your new book. Amen. So be it.

Yes, exactly. Amen. So be it.

FOR MORE INFORMATION:

Visit: https://cac.org/about/our-teachers/james-finley/

Notifications

You can skip to the end and leave a response. Pinging is currently not allowed.